Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim

Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim is a contributing music critic for The New York Times. She is also the founder and artistic director of The Beginner’s Ear where she “uses meditation and sound to help people become better at listening – not just to music, but to themselves and each other” Born to German parents in Brussels, Corinna obtained a B.A. in music and psychology from Royal Holloway College (University of London), an M.A. in Renaissance Theory and Culture and a doctorate from Cambridge University. She wrote her Ph.D thesis on the 17th-century Jewish Venetian poet Sara Copio Sullam. In February 2020 she completed the Mindfulness Teacher Training Program through MNDFL in New York City”. www.beginnersear.com

Full Disclosure: Corinna’s article, featured here, was my initial inspiration for creating this archive of hand annotations.

When Classical Musicians Go Digital

By CORINNA da FONSECA-WOLLHEIM JUNE 9, 2016 , The New York Times

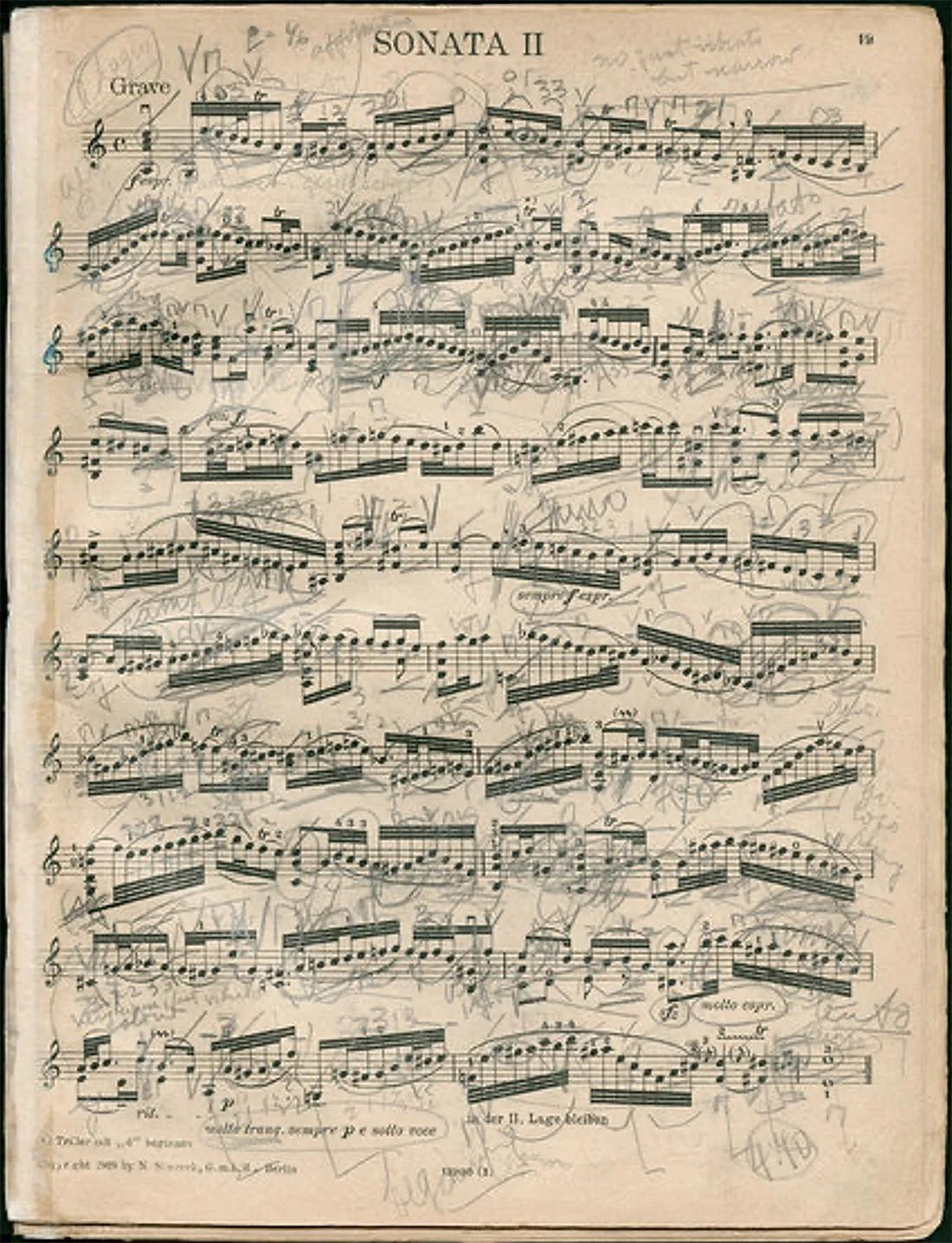

Yehudi Menuhin’s marked-up copy of Bach’s Solo Violin Sonata No. 2. Credit Royal Academy of Music Foyle Menuhin Archive.

Among the exhibits on display at the Royal Academy of Music during its centenary tribute to the violinist Yehudi Menuhin is a single page of a Bach violin sonata. The printed page is darkened with Menuhin’s pencil markings fixing the contours of a phrase, the direction of bow strokes, fingerings, the speed and width of vibrato: the expression, in graphite, of a player’s interpretation and craft.

Peter Sheppard-Skaerved, a violinist and scholar who organized the exhibition, said in an email that the page creates “a sense of ‘digging away’ at the material, almost as if going at it again with the pencil might reveal more, find more of the vein of ore which we all hunt.”

That hunt is still central to the art of a classical musician. But these days there are new weapons. Increasing numbers of players are using iPads and laptops instead of sheet music, especially now that the latest generation of tablets come in the same size as a standard score. And styluses like the Apple Pencil, which was released in November, are beginning to take the place of pencils and erasers.

If, say, in the course of a summer festival, a pianist plays a familiar quintet with a new set of partners, she can save the group’s interpretive markings in a neatly archived file without having to erase her usual dynamics and tempos. A young professional hopping from one master class to the next can keep track of multiple, even conflicting, instructions, traditions and technical tips.

But the advantages of the new technologies aren’t just clerical. Mr. Sheppard-Skaerved pointed out that the advent of the mass-produced graphite pencil in the second half of the 19th century coincided with profound changes in the way a performer engaged with a musical text. The generation of musicians who benefited from the new tool — capable of making durable, but erasable, markings that didn’t harm paper — were, he wrote, “the first where practice was aimed at perfection of execution, and not developing the skills for real-time extemporization on the material in front of them, or improvisation ‘off book.’ before a pop-up concert.

What changes does the new digital technology reflect or enable? Conversations with some of classical music’s most passionate advocates of the gadgets and with developers like forScore and Tonara that write applications for them reveal a number of developments. The traditional top-down structure of teaching has been shaken loose. The line between scholarly and practical spheres of influence is becoming blurred. And the very notion of a definitive text is quickly losing traction — and with it, the ideal of that “perfection of execution.”

An unexpected consequence of the digital shift is that it has brought performers closer to historical sources, including composer manuscripts. The pianist Wu Han, one of the artistic directors of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, said in a Skype interview from Seoul, where she was leading workshops: “It’s not like the old days where you only have information passed down by a teacher. Now everyone is a detective.”

Ms. Wu takes pride in being an “early adopter” of the iPad and can rattle off its benefits to the traveling musician. By her own count, she is performing 42 works this summer. In the past, the attendant sheet music would have filled three quarters of a suitcase. Now she carries an entire library in a sleek tablet. Page turns have become quiet and elegant thanks to a wireless pedal. (Where her enemies were once awkward page turners, they’re now Chinese concert halls with Bluetooth blockers.) She needn’t worry about losing her scores or seeing the paper deteriorate over the course of a long tour. And in master classes, she scribbles notes for her students onto her tablet, saving a separate file for each player.

But what most shapes her music making — the myriad decisions on how to pace a phrase or to build character through articulation and dynamics — is the musicological groundwork of combing through early editions and manuscripts for clues of the composer’s intentions.

Matt Haimovitz setting up his score on an iPad before a pop-up concert. Credit Michael George for The New York Times.

“In the old days, I had to wait until I could go to the library to seek them out,” she said. But now that foundations like the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, Germany, are painstakingly digitizing material, it’s on the internet.

With free downloads replacing expensive and unwieldy Photostats, musicians are increasingly reading music directly from manuscripts. The cellist Matt Haimovitz has been performing from handwritten scores on his iPad, including Schubert’s “Arpeggione” Sonata and Anna Magdalena Bach’s manuscript copy of the suites for solo cello by her husband, Johann Sebastian.

Nicholas Kitchen, a violinist with the Borromeo String Quartet, recalled the frustrations of his early encounters with manuscripts in the days when studying them meant visiting a library’s rare books room and donning white gloves. With his fellow Borromeo players, he now reads the late Beethoven quartets directly off a manuscript, which he can display — and mark up — on his screen. Comparing it with respected printed editions long known as the “Urtext” — the uncontaminated, definitive version of the score as determined by musicologists — he has found all sorts of details that never made it into print.

“In our printed music, we have about nine dynamics, while in the manuscript there about 20 different ones,” he said describing tiny alterations to the single letter p — for “piano,” or soft — that Beethoven

marked. Some have a cross on the stem, for instance, others a double cross. “There are 10 distinctions just in the area of piano.”

The Borromeo String Quartet in 2015. Credit Richard Bowditch

At the same time, the traces of Beethoven’s creative process, with passages crossed out and amended, sometimes with visible impatience, inspire a different kind of playing. For a noted improviser like Beethoven, Mr. Kitchen said, “it was important to react to the page, but just as important was the incredible freedom to go where the ear leads you.”

The composer Dan Visconti, who uses iPads in his work with the Chicago-based Fifth House Ensemble, said the technology is “changing the culture a little bit.” He added: “Now that you can get different versions of sheet music easily, I don’t see performers looking at something and thinking, Oh, this is set in stone. As a result, you no longer have quite the same slavish worship of the text.”

With performers engaging in the sort of sophisticated archaeological work that used to be the province of academics, professional music editors may become an endangered species. Or at least the nature of their work will change, with revised editions released on a more fluid time scale.

But Ron Regev, a pianist and the chief music officer of Tonara, the software company, said he does not believe that the professional editor is going anywhere as long as classical musicians demand high-quality scores. Indeed, the digital age brings with it advantages. “Until now, editors only had one chance to put what they knew into a fixed edition,” he said. “Now you can continually change the score according to the most recent scholarship, and instead of having to reshoot and spend millions on a new edition, you update a file.”

With composers also in on the digital revolution, their own creative process — the drafts, corrections and discarded dead ends that performers puzzle over on manuscripts — is often captured in a sequence of updated files. Mr. Kitchen said that when his quartet workshops a new piece with the composer, changes are sometimes made on the spot and shared wirelessly with the players.

“What we end up with doesn’t at first glance look like the wonderfully expressive sketches of Beethoven,” he said. “But there was a final version, and then the really final version, and perhaps the final, final version. A musicologist someday far from nown will be doing the same thing we do now looking at corrections in a Beethoven manuscript.”

In the cool clarity of the new medium, some things may be lost. The sort of expressionist fury with which Menuhin marked up Bach or the stenciled grace of a Schubert manuscript reveal much about the human behind the artist. Ms. Wu said she enjoyed sorting through the psychological clues earlier composers left behind in their handwritten scores.

“If you have the neat printed score, you don’t see the struggle,” she said. “You can detect how brilliant Mozart was writing individual parts instead of vertically. Mendelssohn’s ‘Songs Without Words’ have those beautiful paintings in them. Today, we don’t know if a composer is messy or meticulous.”

> Return to the Essays & Articles or click below:

Digital Dexterity: Composing on Computer

Should We Still Teach Students To Hand-Write Music?

Notes from the Past - Annotations on the Musical Score

How Much Is Too Much When Writing on Sheet Music?